I’m now back from Melbourne, and staying put for the rest of the year, finishing off my book. I’m about halfway through the “House of Odd” inks, and it’s a good feeling to be close to the finishing line! I’m looking forward to finishing the inks at the end of this month.

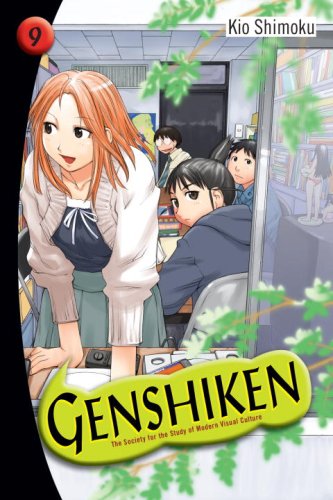

While I’m at it, I’m making another manga recommendation, this time for something a bit different to what I usually read. If I must describe it in a sentence, I will call it a “character-centered dramedy about Japanese Otaku culture” – aka Genshiken. Otherwise known as “the Society for the Study of Modern Visual Culture”.

Genshiken (Kio Shimoku)

Genshiken (Kio Shimoku)

(9 Volumes, though it’s continuing in a 2nd series)

NB. “Otaku” is the Japanese word for “fan”, denoting anyone who is an obsessive fan of anything. In this instance, nearly all the characters in Genshiken are Otakus of manga, anime and video games. In English, the word “Otaku” mostly refers to manga/anime obsessives, though in Japan it’s used in all instances that involve crazy fandom.

Genshiken was published by Del Rey in English, and boy, am I glad they translated it, because this would otherwise have completely flown under my radar. For some reason, while I’ve seen much more obscure fare in Chinese translations, I’ve not once seen this manga in Chinese stores. Which is… strange. Perhaps it’s too culturally-specific for Chinese audiences to care, whereas English readers will consider this study of Japanese Otaku-ism as a very “hip” reading experience. Mind you, if you’re looking for a window into the lives of Japanese Otaku, this is a very accessible and very well-written series.

Plot

The main character of Genshiken is freshman Kanji Sasahara, who finally fulfills his long-held dream of joining an Otaku club. The club he joins is called “Genshiken”, short for “the Society for the Study of Modern Visual Culture”, filled with a variety of interesting characters who all share a common obsession – Manga, Anime and Video-gaming. For Kanji, it’s his first time openly hanging out with like-minded people, and he forms a bond with them, eventually learning to accept the parts of himself he was always ashamed of. Especially when he sees the antics of other members who join after him – including fanboy Kousaka, who despite being a hardcore Otaku, is very, very good-looking (and very, very strange).

Kousaka attracts a “normal” to the club, a strong, opinionated young woman called Saki Kasukabe, who has had a crush on Kousaka ever since they grew up in the same neighbourhood. Running into Kousaka again in her freshman year surprised Saki, but she was appalled when she discovered what he was now into. Undeterred by the weirdness of the Genshiken folks, Saki pursues Kousaka relentlessly, trying to “normalise” him, to little success. Saki’s trials and tribulations with Kousaka becomes the story’s second thread, as she is lead on a crash-course through cosplay, conventions, video-gaming, figurine-collecting and other staples of the Otaku lifestyle.

Why I Recommend this Story

Genshiken’s genius lies in its accessibility, which sets it apart from other manga about Otaku culture. People reading this blog will know what an “Otaku” is because I explained it above, but generally when you talk to other people about “Otakus”, you get 3 possible reactions: (a) incomprehension, (b) interest if they are American and into manga/anime culture, and (c) a vaguely-disgusted look if they’re Japanese and not interested in manga/anime. You see, Otaku-culture may be Japanese in origin, but these people are considered social outcasts in Japan.

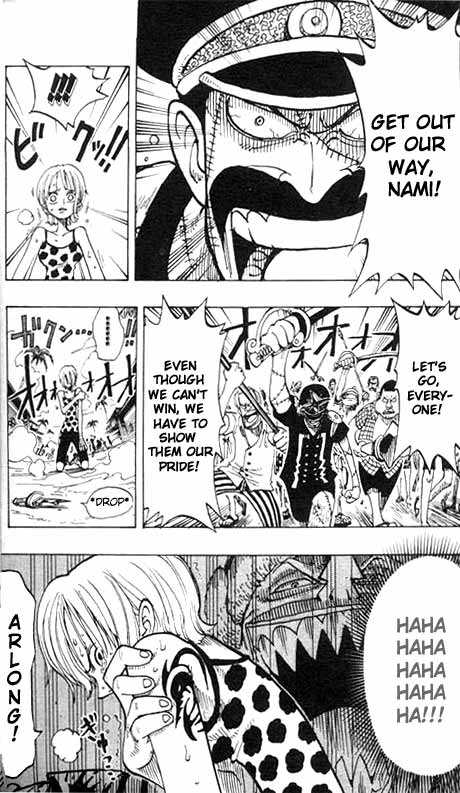

I actually sorta agree with Madarame here (skinny guy with glasses).

Unlike other countries where Japanese pop culture has taken root, Japanese Otaku are like Trekkies or Furries – they are looked down on by the general populance as unbearably geeky and socially-challenged. Genshiken is well-aware of this, and instead of telling the story from the perspective of a down-trodden fan, it tells the story of a “normal” who has stumbled into this gathering of freaks and geeks, and due to reasons outside her control, is forced to (grudgingly) hang-out with them, and even try to understand them. Saki Kasukabe and her clashes with her Otaku “friends” is what gives Genshiken a lot of its human comedy, and to Kio Shimoku’s credit, he never softens Saki, and never makes her into a would-be fan who is just waiting to be converted by the “right” anime. At the end of the series, Saki is still resistant to Otaku culture, but she is now willing to overlook and accept what was once so irritating to her. Likewise, all the other characters grow and change throughout the series, and it’s rewarding (and a little sad) to watch them survive their university days and enter the workforce.

Genshiken has a great sense of its characters, who are a varied bunch. Many of them feel like “types” you would encounter at a fan convention, and their interactions has a feel of the “real” about it. Certainly the creator has spent a great deal of time hanging out with Otaku, and if you’ve done the same, you would probably smile in recognition at some of the scenes. The environments also have a wonderful sense of the clutter that such people would collect in their obsessive hunt for the right “doujinshi”, and the meeting room for the Genshiken folks is rendered in loving detail – possibly from a photo of such a meeting room in real life. The dorm rooms of its members, the shops in Otaku central Akihabara, the mass gathering-place of Otakus on their yearly pilgrimage – these are all drawn with a level of care that underscores how much of this series is grounded in the real (if not exactly reality).

Like all good things, Genshiken does come to an end, a satisfying conclusion at a short 9 volumes. I wonder why the series isn’t longer, because I certainly would have liked to see what the characters did when they became fully-functioning adults (as full-functioning as these kinds of people can be). Perhaps that’s why there’s a second series, separate to this first one, that follows these characters while making room for new, younger members. Personally, I haven’t read it, but I would be looking out for it if it were available in English.