- This post is part of a on-going series called “Being a Professional Manga Artist in the West“. The first post is here.

- Buy my short story collection from Bento Comic’s Smashwords storefront @ US$4.99.

Part 5: Comics-Prose with ‘Small Shen’ (2011-2012)

In 2010, I was winding down in terms of illustrating for Dean Koontz. I was on the way to doing three books with them already, and I was looking for a change, which amazingly, did come at the right time. A nice lady called Kylie Chan approached me at a convention, and asked me to do a graphic novel version of a short story she had written called ‘Small Shen.’ It was the prequel to her best-selling Chinese fantasy series called ‘White Tiger,’ which had sold very well in Australia. I was about to draw the third ‘Odd Thomas’ book for Dean, so I had to push her back, but I eventually started working on ‘Small Shen’ in 2011, for Kylie’s publisher Harper Collins Voyager.

‘Small Shen’ was different to all the other manga I’ve done – it’s actually a mix of prose and comics. This may sound a highly unusual step, but Kylie was very supportive, and I also have other reasons to go into this mix and experiment with the format of comics. Part of the reason was because I also felt that comics, my own work included, was getting stale. The other reasons are far more complex, and it has to do with a mixture of economics and issues with production.

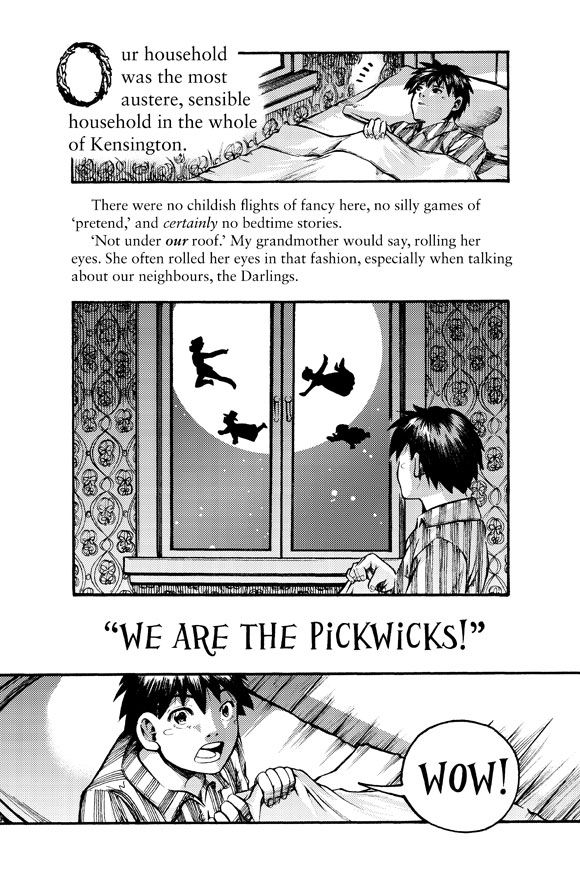

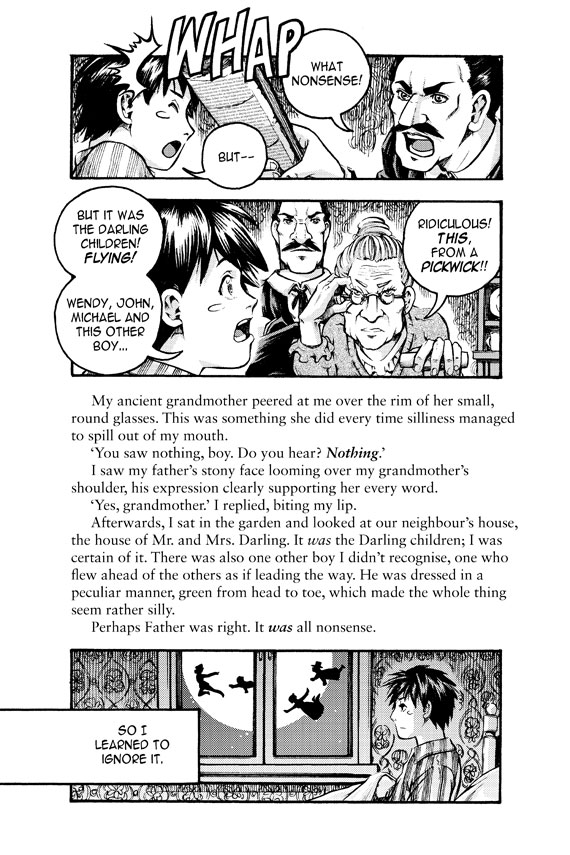

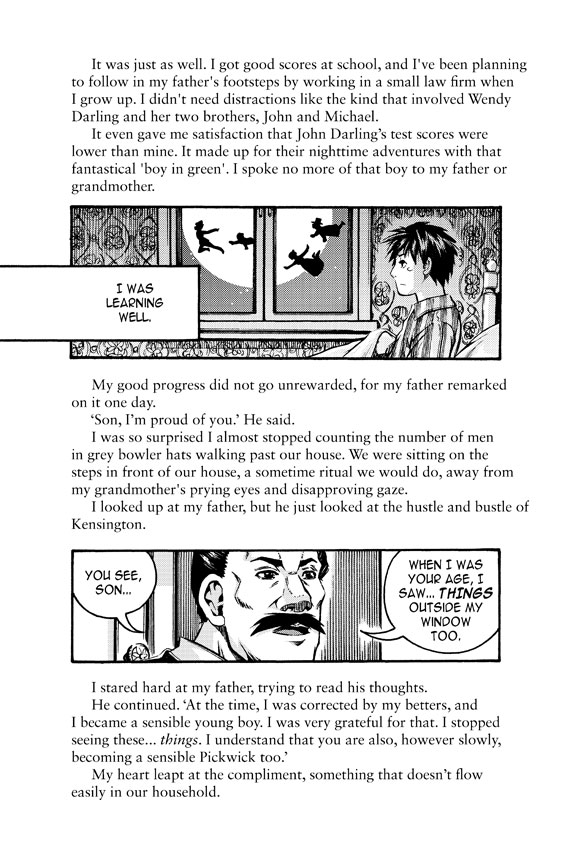

For folks who are wondering what “comics-prose” is, I have a few sample pages here. It’s basically a mix of prose and comic panels, arranged in a way that mixes the two together into a single, seamless, INTEGRATED narrative. Here’s some pages from “We are the Pickwicks” below.

“Comics-prose” is both comics and prose. If you ask me, it leans more towards comics than towards prose, in terms of execution (if not reading experience, which is different for everyone). For those who want to read stories told in this style, here’s more:

- “We are the Pickwicks” (10 pages)

- “Small Shen” (Written by Kylie Chan, chap1-3)

- “Legend of Zelda: The Edge and The Light (312 pages)

————————–

————————–

*****

Either way, working in comics-prose has been fun and exciting, and I’ve since discovered it to be a new and complex way of visual story-telling. But first, I should FINALLY tell you about two minor events that shook me up in 2010, and how it made me question the path I’ve been on (which will be next Monday).