Click here to read the next page –>

This is a follow-on essay to my post called Comics-Prose – “We Are The Pickwicks”. Please read that first before you read this essay.

While illus-writing We are the Pickwicks, I had a lot of thoughts about story-telling that involves comics, and also the future of the comics industry. It has given me pause, and so I put my thoughts down, to share with everyone. Most of what I say is unique to my own experience, but that’s often where a lot of epiphanies start.

Comics are Slow and Expensive to Create

I first started drawing comics in 1998, and has been working professionally since 2004. I’ve noticed that during this time, while my art and stories have (hopefully) improved, the SPEED at which I produce comics has plateaued. It doesn’t help that I draw manga-style comics, which means that the story-telling is stretched out – I tell stories as slow as I always have, hampered by the speed at which I draw, and little can be done about it. In Japan, top manga artists solve that problem by having scores of assistants hanging off each arm, but this hardly means anything to me, since (a) living in Sydney, I realise I will never have a roomful of assistants like the Japanese do, and (b) the assistant system is breaking down, even in Japan. In fact, manga sales is in steady decline in Japan, and has been for some time.

Now, there’s many reasons why the Japanese manga industry is in a tailspin, and it’s the usual bugbears of “alternative entertainment choices” and “piracy”. There’s also the slow-paced, 20-pages a week story-telling, which no amount of record-breaking sales seem to be changing. Eichiro Oda of the mega-selling manga “One Piece” may have truckloads of assistants and enough money to create his own country, but still, only 20 pages of “One Piece” come out each week, and he’s taken 15 years to tell just half of “One Piece”. I did the calculations for my own life: even if I draw every day, the best I can produce is ONE 200-page volume a year, which means I only have 50 more manga volumes I can produce in this lifetime. Less, if I want an actual life that involves sunshine and social activities.

Problems with Modern Manga

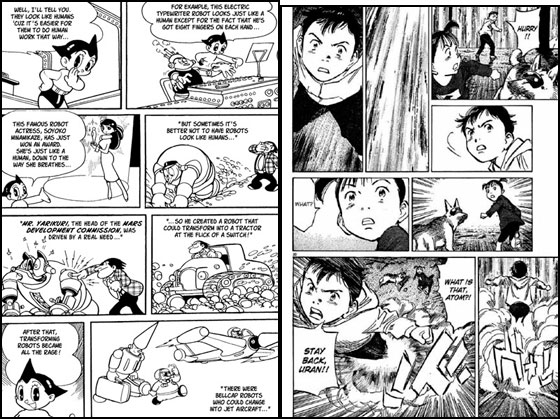

This is a limitation of the Japanese system, but it’s also a limitation of the form. I read “One Piece” each week, but while I enjoy the story, I’m getting tired of the slow pace at which the story comes out. Oda packs more plot and action into a SINGLE issue of “One Piece” than any other manga artist I’ve seen, but that just illustrates the problem with modern manga – compare it with Osamu Tezuka’s manga (Astroy Boy, Black Jack) from the 60s and 70s, and you can see the story-telling in manga was much more compressed back then than it is now. Tezuka’s manga simply had many more panels in a single page, simpler artwork, and a more straight-forward way of telling a story. Since Tezuka’s time, manga has become more artistically complex, with much less panels on a page, and requiring a larger number of pages to tell the same story.

Common sense may suggest a return to Tezuka’s style of story-telling, but that’s missing the point. Audiences have moved on since the 60s and 70s – Tezuka’s stories may have been excellent, but his art and story-telling is dated to the point where most modern readers find it unacceptable. There’s nothing you can do when readers demand a certain level of complexity in the art; you either deliver it or they lose interest, and when you struggle to deliver that art, you start going a little crazy from the overwork, your health suffers, and worse of all, you can get burnt out from it.

More Story in a Single Issue, Taking Less Time to Draw

Does that mean writing prose is easier? I’ve always considered myself a story-teller first, irregardless of medium, but I went into comics to tell stories in picture form, and the idea of telling stories without pictures just make me sad. At least one advantage comics will always have over other forms of visual entertainment is the cost – it’s always much cheaper to create comics than it is to do film or video games.

To me, perhaps the only setback with comics is that it takes so much time and money to produce the comics equivalent of a few prose chapters. That was one advantage prose had over comics, and I wanted some way to marry the best things about prose as a medium, with the best things about comics as a medium. Which is why I decided to start creating stories in comics-prose format. To me, it means more story in a single issue, while taking LESS time to draw – as a story-teller, it seems to me a logical step to move in. Readers also get more story for less money, while still getting a strong visual element.

Just Who Is Comics-Prose Intended For?

It’s a delicate balance to maintain, but it’s definitely doable, and some may also see comics-prose as a bridge between comics and prose. Personally, I think that’s perfectly fine – comics-prose is both prose and comics, which makes it an either/or. It’s important to make this point clear, because even though it seems new and different, comics-prose actually isn’t that much different from conventional prose or comics. Ultimately, the goal is to expand what counts as “comics”, and thus expand the readership of comics.

(Obligatory) Conclusion

Some people may also question whether prose readers will take to graphic prose, but after working with Dean Koontz and now Kylie Chan, I would say that the average prose reader has no problem with comics. The sales figures of the Odd Thomas graphic novels seem to suggest Dean’s fans are fine with comics as long as they’re not difficult to read – and while there are a few vocal “book snobs”, they’re in the minority. Most people, especially children, increasingly tend to see a book as a book, irregardless of whether there’s pictures inside or prose. Certainly, the acceptance of graphic novels into mainstream culture has only helped this attitude.

2 thoughts on “Comics-Prose”

Comments are closed.